animal dilemmas

Who do we see as deserving our moral concern?

Introduction

Who do we consider when making everyday moral decisions? Family? Friends? Strangers? What if there is more to the story?

One way to conceptualise this is through the idea of the ‘moral circle’ (Singer, 2011). This refers to who we see as deserving of our moral attention. Historically, it has been argued that this circle is constantly expanding, from our close relatives to eventually include pets, wild animals and even nature itself, such as trees and plants. But how do we really draw these circles, i.e. who do we separate into ‘us’ and ‘them’, and why?

This theoretical notion of moral circles has taken shape in the form of the Moral Expansiveness Scale (MES) (Crimston et al., 2016), developed by Charlie Crimston et al. This scale enables us to measure how far people extend their moral concern. Since then, this measurement method has been used as a standard to test moral closeness. For example, it has revealed some variability in the types of entities that people feel closer to, with some surprising results. For instance, Joshua Rottman’s research has demonstrated how some individuals view animals and nature as more akin to themselves than to members of the outgroup (Rottman et al., 2021).

Lately, however, there has been a shift in focus. Traditionally, the focus has been on investigating which entities are closer to us, but not on investigating who the ‘us’ is, i.e. which types of people prioritise which types of entities. And this leads us to ask: how does our identity shape who we see as deserving of our moral attention? Aspects such as age, gender, nationality, and even political preferences can play an important role in determining what we perceive as worthy of our moral concern. Bernhard Jaeger and Matti Wilks have investigated exactly this, highlighting the traits of the entities judged, and who is making the judgement. According to them, the interaction between these two factors can explain a large proportion of the variability in our moral concern (Jaeger & Wilks, 2023).

Despite the growing body of research in this area, most previous studies have relied on self-reported ratings from participants. Only a handful of studies have adopted a behavioural approach. An example of this is the work of Aurélien Miralles et al. They found that empathy and compassion are influenced by evolutionary distance. The closer an entity is to humans genetically, the more moral concern people tend to feel towards it (Miralles et al., 2019).

Our research

Following this line of research and, more specifically, this behavioural-based approach, we designed two studies. Our aim was to investigate how people cognitively structure the different entities that make up their moral world.

To achieve this goal we tested how people resolve dilemmas in which they must choose to save one of two entities when presented with visual stimuli, i.e. images of the entities to prioritize in question. In the first experiment, we focused on testing how these decisions are made individually and how they can be linked to aspects of our identity, such the willingness to donate to a charity. In the second experiment, we investigated whether the value we attribute to these entities is fixed or relative, based on the framing of the task: saving/prioritizing individual entities or groups of entities.

Study one

In the first study, participants completed a one-factor, two-alternative forced-choice task; in simple terms, they were presented with various hypothetical emergency situations and had to select which of two entities they would save. Their choices and reaction times were recorded. At the end of the experiment, participants were offered the chance to enter a real lottery with five prizes of £10. Following this, they could decide whether to donate part of their potential winnings to a fund focused on animals, humans, or the environment, or not donate at all.

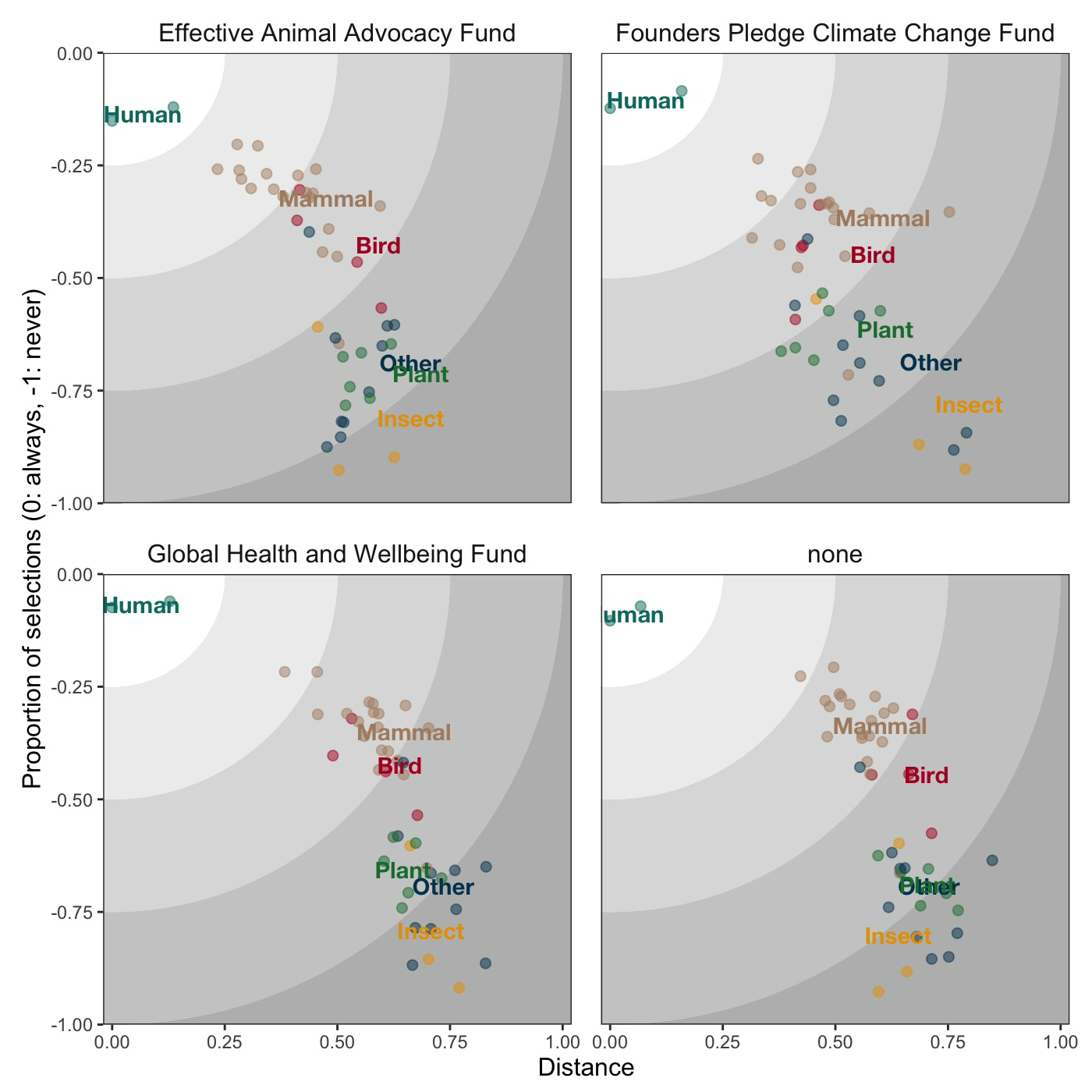

Using these three sources of information: choice (which entity was ‘saved’), response time (how long it took to select the entity), and the charity to which they decided to donate (or not to donate), we performed a multidimensional scaling analysis. This method enabled us to take information about how similar or different these entities were perceived and turn it into a map.

Two key findings emerged. The first is a clear pattern in the prioritised entities. Overall, people tended to feel closer to humans, followed by other animals such as mammals, birds and cephalopods, and then plants, molluscs and insects. However, there were also some identity-based disparities, for example in the charities participants chose to donate to.

Participants who chose to keep their lottery winnings for themselves, i.e. non-donors, and those who decided to donate some of their winnings to a fund aimed at helping other people showed a moral hierarchy where humans were the only entities prioritised. There is a significant disparity in the moral prioritisation (y-axis) and moral proximity (x-axis) between humans and other entities, with minimal variation observed across other categories of entities. This suggests that these group of participants categorise humans and other entities as fundamentally different in terms of moral concern.

On the other hand, although humans were still prioritised morally by participants who decided to donate some of their winnings to an environmental or animal welfare fund, there was a shift in how closely related those participants perceived other entities, such as animals and plants, to be. Environment-based donors showed relatively higher support for plants than other groups of participants, and they felt closer to a wider range of entities. Among donors to the animal fund, there was almost no difference in moral prioritisation (y-axis) and moral closeness (x-axis) between humans and other entities.

In light of these results, we wanted to investigate whether the way the question is framed can influence how we value these entities. This is what we explored in the second experiment.

Study two

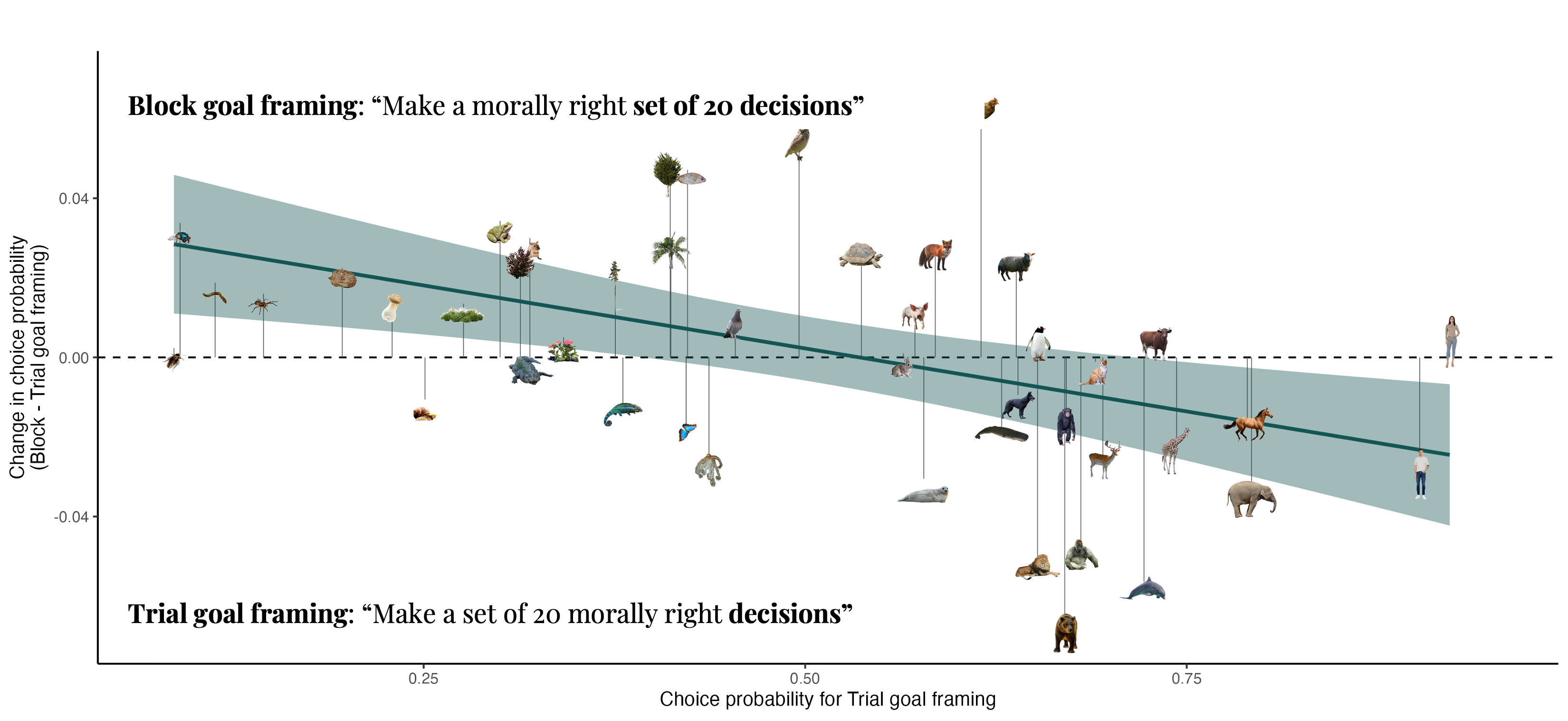

In this second experiment, we investigated whether the value we attribute to entities is fixed or relative, i.e., if it is always the same or if it depends on how the task is framed: saving or prioritising individual entities or groups of entities. To achieve this, we adapted the design of the original experiment: participants could either make one large decision to save 20 entities, or 20 smaller decisions to save one entity each. We were interested to see whether the value of the entities would differ depending on how the dilemma was framed.

The findings indicate that, despite the presence of some similarities between the two frames (i.e. the entities that fall on the 0 on the y-axis), there are subtle variations in the moral value of other entities.

When instructed to make individual decisions, participants tended to prioritise familiar, charismatic and historically close entities such as elephants, dolphins, pets, chameleons and butterflies. However, those making group decisions prioritised less appealing entities, such as insects, plants and some other animals. What was most noticeable was that the more an entity was saved in the group frame, the less it was saved in the individual frame, and vice versa.

This suggests that the framing of the decision might encourage people to make room for entities that may not be particularly charismatic, familiar, or close to us, yet are essential maintaining ecological balance, biodiversity or in general a greater wellbeing.

In conclusion, adopting a broader perspective, one that looks at the whole rather than isolated decisions, can lead to the inclusion of otherwise overlooked entities.

References

2023

- Cognitive ScienceThe Relative Importance of Target and Judge Characteristics in Shaping the Moral CircleCognitive Science, 2023

2021

- Cognitive ScienceTree‐Huggers Versus Human‐Lovers: Anthropomorphism and Dehumanization Predict Valuing Nature Over OutgroupsCognitive Science, 2021

2019

- Scientific ReportsEmpathy and Compassion Toward Other Species Decrease with Evolutionary Divergence TimeScientific Reports, 2019

2016

- JPSPMoral Expansiveness: Examining Variability in the Extension of the Moral WorldJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2016

2011

- Princeton