the practical reason project

What is considered reasonable? And normal?

Introduction

What does it mean to be a reasonable person? We often encounter situations in which something seems reasonable: it feels intuitive, advisable and desirable. But what does it mean to be reasonable? In law, the term ‘reasonable person’ is a legal fiction that is used to determine how a prudent and rational individual would act in a given situation (Bongiovanni et al., 2009). However, since the end of the last century, this term has been used considerably more frequently in everyday language (Tobia, 2018, p. 353).

There has been a long-standing debate about how this legal fiction and lay usage are formed. According to Holmes (Holmes, 1881) the concept of reasonableness can be defined as the average, which is determined by the habitual actions of real people. Conversely, alternative proposals regard reasonableness as prescriptive, i.e. as a moral order based on a particular moral principle. However, recent research posits that the phenomenon may be defined by a combination of both influences. Kevin Tobia proposes a dual perspective of reasonableness, positing that it should not be regarded as purely descriptive or prescriptive, but rather as a hybrid judgement that incorporates statistical and prescriptive considerations (Tobia, 2018, p. 45).

A parallel approach has been proposed for what we think is normal. Some research propose that what we think is normal is a hybridisation of frequencies from a single descriptive-prescriptive spectrum. The approaches to the descriptive-prescriptive divide vary; some are guided by concepts such as ‘the good’ and ‘the common’ (Wysocki, 2020), while others are informed by concepts such as ‘the average’ and ‘the ideal’ (Bear & Knobe, 2017). In essence, what is considered normal can be regarded as a combination of what is common or average, and what is good or ideal.

Our research

In this project, we are investigating how these four properties (what is average, ideal, normal and reasonable) can be understood in relation to each other. We are examining them in terms of frequency estimation (study one, i.e. what is the average/ideal/reasonable/normal amount of different things) evaluation (study two, i.e. how favourably or unfavourably these frequencies are), and cognitive accessibility (study three, i.e. how quickly do these frequencies come to mind?).

Study one

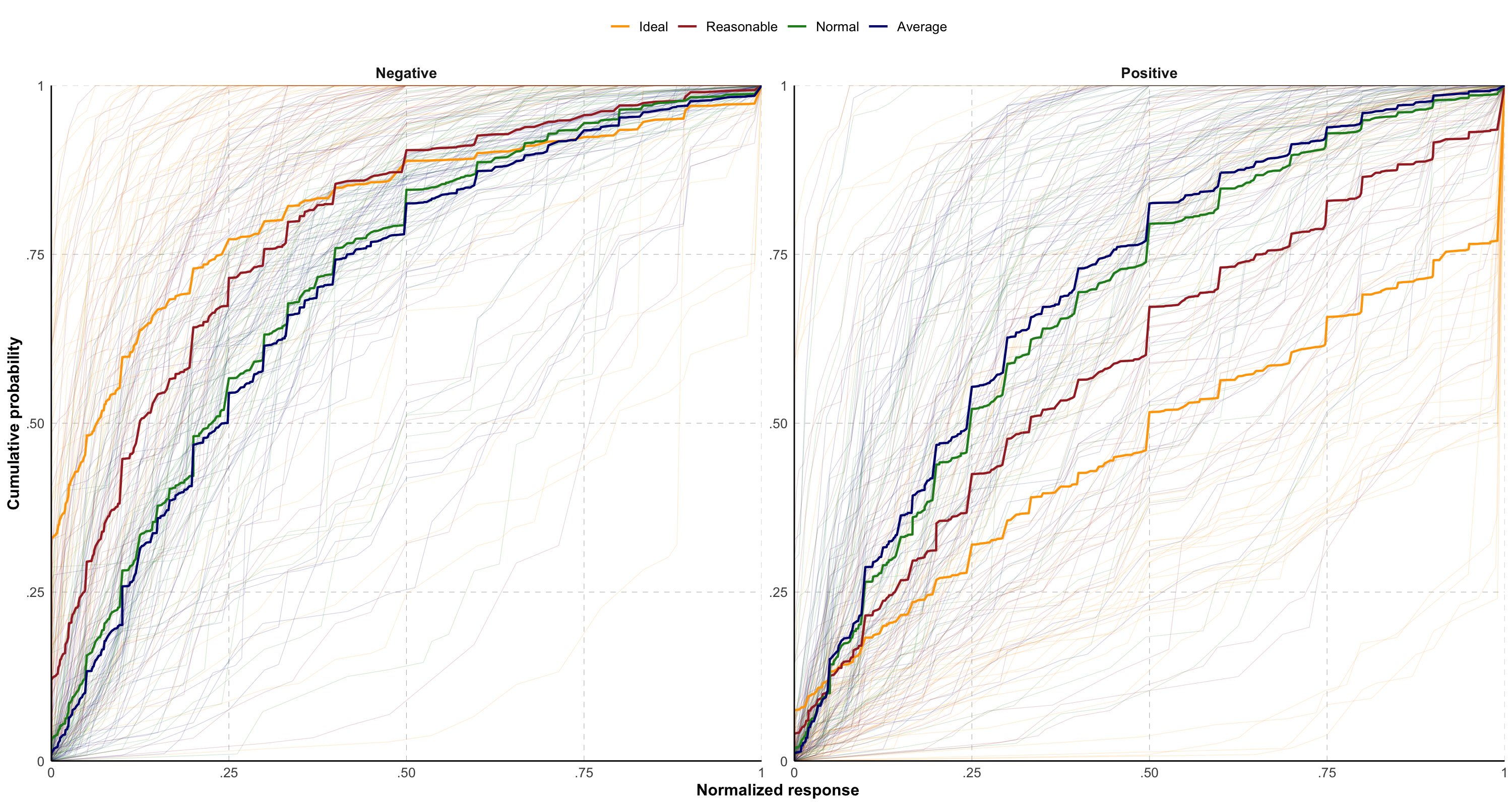

In this first study, we asked participants to estimate the average, ideal or reasonable amounts of various things.

This first study reveals a clear pattern of intermediacy in reasonable and normal estimates. In other words, our perception of what is reasonable and normal is a combination of what we perceive to be average and what we consider to be ideal.

This effect was consistent across 100 different positive and negative actions and behaviours. For example, when asked to estimate the reasonable number of times a person exercises in a gym per week, people’s answers can be predicted by what others perceive as average and ideal. A similar effect was observed with normal amounts.

More precisely, we saw how normal estimates were primarily influenced by what people considered average. And for reasonable estimates, however, the picture was more balanced: participants appeared to consider average and ideal aspects equally when determining what they felt was reasonable.

Study two

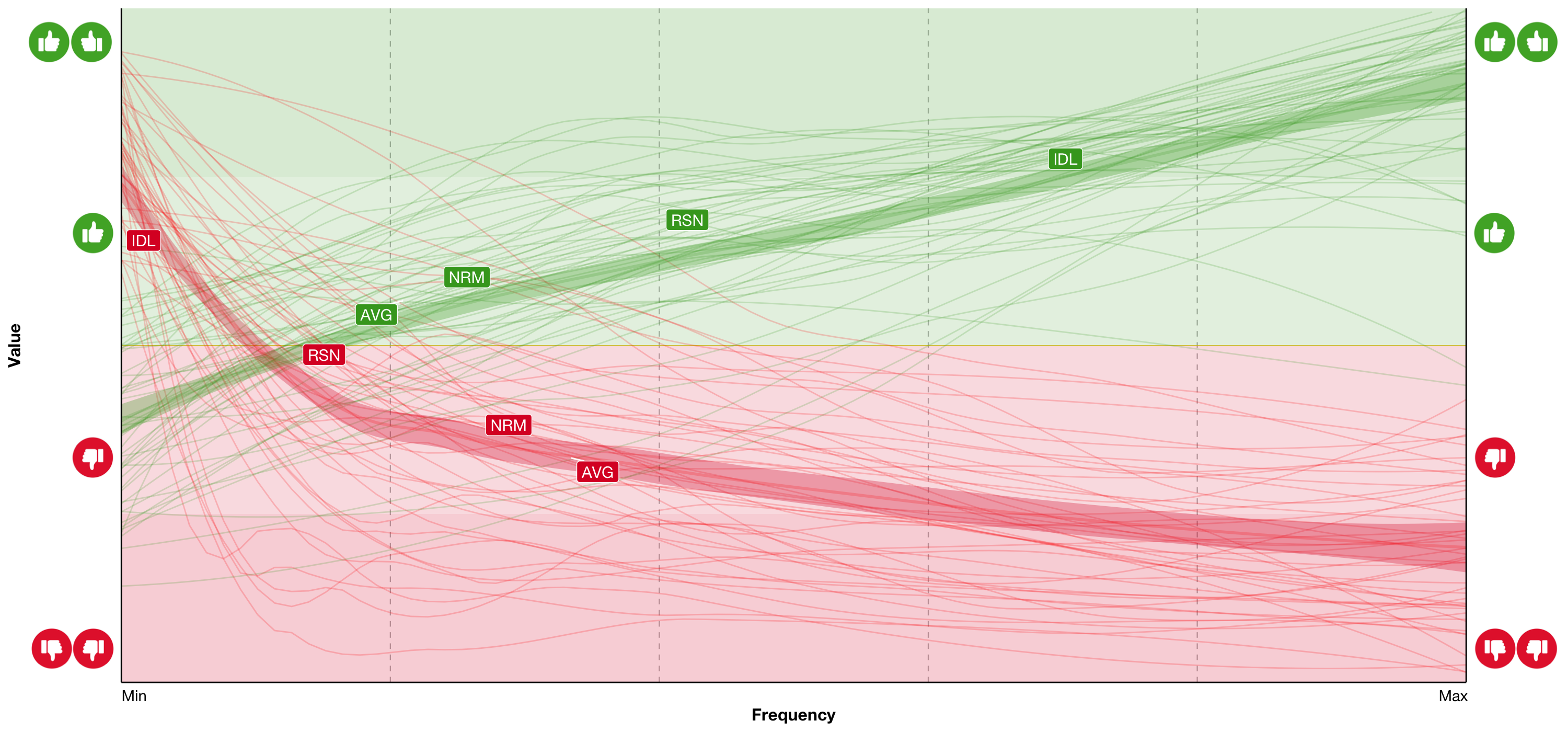

In our second study, we explored how people evaluate average, ideal, normal, and reasonable frequencies of various things.

Participants were shown the frequency of a behaviour. For example, ‘Number of times a person exercises in a gym per week: Three times”. This frequency corresponded to one of four estimations (average, ideal, normal or reasonable) in the first study. However, the participants did not know which property they were evaluating. They were simply asked to rate how favourable or unfavourable they found the frequency for that specific item.

The results showed clear differences in the evaluation of the four properties. Specifically, the findings showed that average frequencies are evaluated least favourably, followed by neutrality/negativity towards normal frequencies. In contrast, frequencies within the reasonable range were more likely to be evaluated favourably.Ideal frequencies were wvaluated more highly.

The results of the second study indicate two things. Firstly, moral expectations are similar for normal and average frequencies. Secondly, people are less demanding when considering reasonable behaviours and events than ideal ones. This suggests that people’s perception of what is reasonable is an adjusted ideal, i.e. a contextual guideline that aligns with what would be ideal, but without all the unattainable demands (consistent with (Tobia, 2018, p. 331)).

Study three

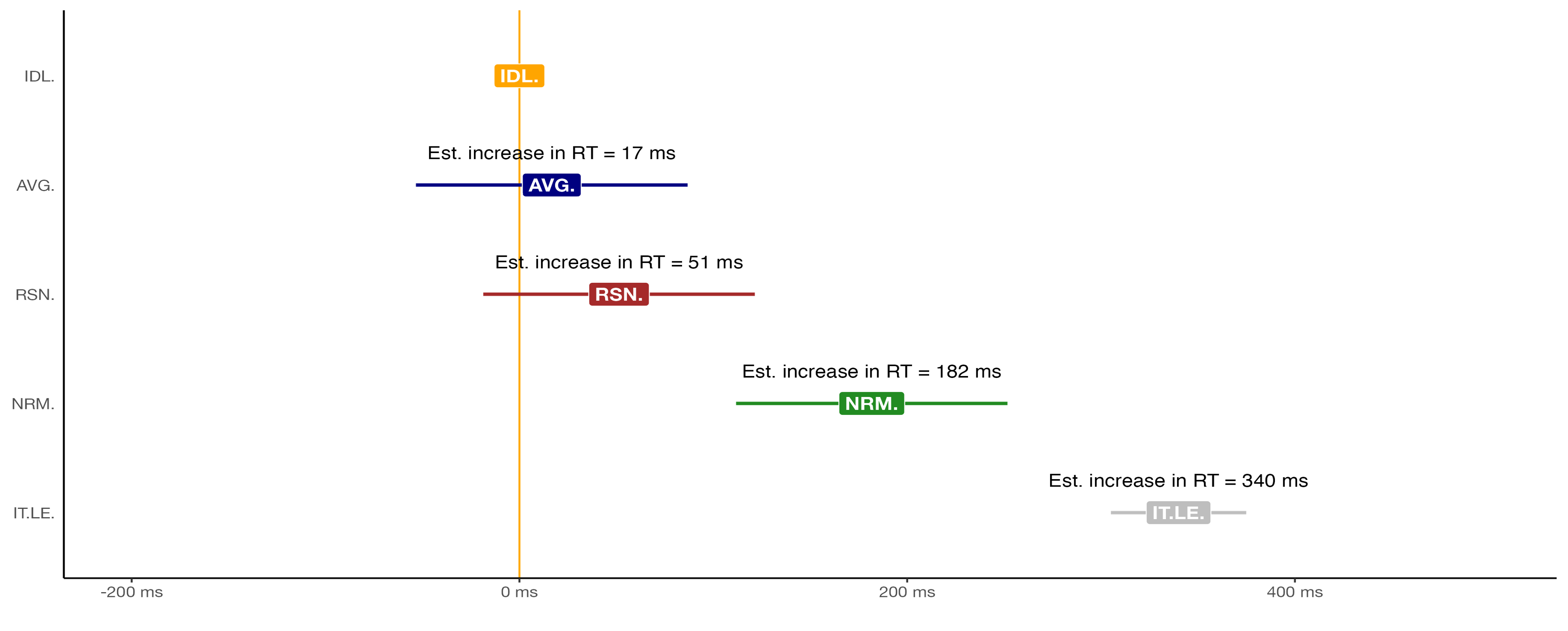

Lastly, in our third study, we explored how long it takes them to think about what is average, normal, reasonable or ideal for a given behaviour or action. Do some of these properties take longer to retrieve than others? If so, what does this tell us about how intuitive or accessible each type of judgement is?

We found that ideal and average estimates were recalled the fastest. However, it was surprising that there were no statistically significant differences in the time taken to retrieve ideal, average or reasonable frequencies. By contrast, normal estimates really stood out, it consistently taking longer to retrive.

Importantly, reasonable was processed just as quickly as ideal and average, which may indicate that reasonable, though also hybrid, is more mentally accessible or clearly defined than normal.

References

2020

- RPP

2018

- SSRN

2017

- Cognition

2009

- Springer

1881

- CommonLaw